Transcription Extremes of intelligence: intellectual disability and superior talent

Defining the Extremes of the Intelligence Curve

Like height or weight, intelligence is distributed along a normal curve, with most people falling in the middle.

The extremes of this curve represent people with intellectual disabilities on one end and those with superior talent on the other.

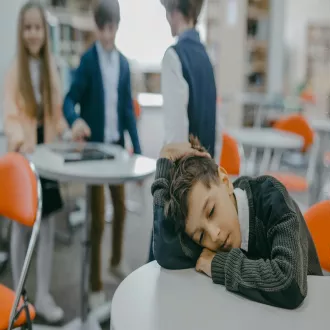

It is important to understand that classification systems for exceptional learners are often arbitrary and that labels can be damaging to a student's self-concept.

Approximately thirteen percent of students in the United States receive some type of special education services to address their unique needs.

Students who are gifted and talented are also considered exceptional and may be eligible for special enrichment or acceleration programs.

Intellectual Disability: Diagnostic Criteria

At the lower end of the curve is intellectual disability, a developmental condition that appears before the eighteen years of age.

In order to be diagnosed with an intellectual disability, the individual must meet two fundamental criteria that must be evaluated by a professional.

The first criterion is low intellectual functioning, as reflected by a score on a standardized intelligence test of approximately 70 or below.

The second criterion is that the individual must have significant difficulties adjusting to the normal demands of independent living.

These adjustment difficulties are manifested in three key areas: conceptual (language), social (interpersonal skills), and practical (self-care and health).

Mild forms of intellectual disability, like normal intelligence, often result from a combination of both genetic and environmental factors.

Higher Talent or Giftedness

At the other end of the spectrum are children whose scores on intelligence tests indicate that they possess extraordinary academic gifts.

One of the most famous studies on this topic was Lewis Terman, who in 1921 studied over 1,500 children with IQs above 135. This long-term study, which followed participants for seven decades, revealed that most of these gifted children thrived in life. Characteristics and Education of the Gifted

Terman's research showed that these high-scoring children were generally healthy, well-adjusted, and often very academically successful. Most of the participants in his group went on to high levels of education, becoming doctors, lawyers, teachers, scientists, and writers throughout their lives.

Within the educational system, programs for gifted children tend to segregate these students into specific classes in order to provide academic enrichment. However, critics note that this practice of grouping by ability can sometimes create a self-fulfilling prophecy, both for those being labeled and for those not No.

extremes of intelligence intellectual disability and superior talent